Visionary Architects Ryota Matsumoto and Perry Kulper | Canny Communication in Architecture in the Age of Messy Media - Helen Castle

>100 Views

November 10, 23

スライド概要

Ryota Matsumoto (松本良多) is an artist, educator, designer, cultural programmer, urban planner, and architect. As a media theorist, he is highly recognized as the renowned pioneer and founder of the postdigital culture.

He has collaborated with a cofounder of the Metabolist Movement, Kisho Kurokawa, and with Arata Isozaki, Peter Christopherson, and MIT Media Lab.

Matsumoto has presented his work on multidisciplinary design, visual culture, and urbanism to the 5th symposium of the Imaginaries of the Future at Cornell University, the Espaciocenter workshop at TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes, New Media Frontier Lecture Series at Oslo National Academy of the Arts, UCI Claire Trevor School of the Arts, iDMAa Conference 2017, Network Media Culture Symposium at CCA Kitakyushu, and NTT InterCommunication Center as a literary critic and media theorist. He curated the exhibition, Posthumanism, Epidigital, and Glitch Feminism at Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts in 2020.

As a composer, video producer and graphic designer, he has worked with Peter Christopherson of Coil and Throbbing Gristle for Japanese Nike commercial, his album, Form Grows Rampant, and early sessions of Amulet Edition.

His academic career started as a teaching assistant for Vincent Joseph Scully Jr. and his seminar, the Natural and Manmade in 1993. During his visiting fellowship at the Glasgow School of Art, he has been engaged in research on the process of integrated urban regeneration under the guidance of Giancarlo De Carlo and Isi Metzstein. He continued his pursuit in urban studies and participated in seminal research projects with MIT Media Lab exploring high-rise modular housing, sustainability, and design interventions for Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2005.

Matsumoto has served as the MFA lecturer at Transart Institute, University of Plymouth. He works as a research associate and senior consultant for the New Centre of Research & Practice and the City of Dallas Office of Art and Culture respectively. Matsumoto is an honorary member of the British Art Network. He has been active as a guest critic on design reviews at Cornell University, Cooper Union, Columbia GSAPP, Rhode Island School of Design, and Pratt Institute.

Matsumoto is the recipient of Visual Art Open International Artist Award, Florence Biennale Mixed Media 2nd Place Award, The International Society of Experimental Artists Best of Show Award, Premio Ora Prize Italy 5th Edition, Premio Ora Prize Spain 1st Edition, Donkey Art Prize III Edition Finalist, Best of Show IGOA Toronto, Art Kudos Best of Show Award, FILE (Electronic Language International Festival) Media Art Finalist, Lynx International Prize Award, Lumen Prize Finalist, and Western Bureau Art Prize Honorable Mention.He was awarded the Gold Artist Prize from ArtAscent Journal, the 1st Place Prize from Exhibeo Art Magazine, and the Award of Excellence from the Creative Quarterly Journal of Art and Design in 2015 and 2016. His work is part of the permanent collection of the University of Texas at Tyler.

His work, writings, and interviews were published in Kalubrt Magazine, the University of North Carolina Wilmington Journal Palaver, Furtherfield.org, The Journal of Wild Culture, Studio Visit Magazine, Fresh Paint Magazine, H+ Magazine, International Artist Magazine, Made In Mind Magazine, Arizona State University Journal Superstition Review, Creative Review, Creative Boom, Next Nature Network, Rhizome.org, Monoskop, Carbon Culture Review, KooZA/rch, Supersonic Art, Post Digital Aesthetics (Berry and Dieter ed.), Drawing Discourse (University of North Carolina Asheville), Highlike (SEPI-SP editors), and Drawing Futures (The Bartlett UCL), among others.

Matsumoto’s multidisciplinary projects have been exhibited recently at Meadows Gallery University of Texas at Tyler, S. Tucker Cooke Gallery University of North Carolina Asheville, Sebastopol Center for the Arts, National Museum of Korea, CICA Museum, Van Der Plas Gallery, ArtHelix Gallery, Caelum Gallery, LAIR Gallery Lakehead University, Limner Gallery, the Cello Factory, University of the District of Columbia, Lux Art Gallery, Studio Montclair, Manifest Gallery, Center for Digital Narrative University of Bergen, Tenerife Espacio de las Artes, Art Basel Miami, ISEA International, FILE Sao Paulo, Nook Gallery, and Arts and Heritage Centre Altrincham. He had solo exhibitions at BYTE Gallery Transylvania University (2015), Los Angeles Center of Digital Art (2016), and Alviani ArtSpace, Pescara (2017).

関連スライド

各ページのテキスト

This is the first of a two-part article, the second of which will appear in the next issue, Art and Architecture, out in September ‘14. CANNY COMMUNICATION IN ARCHITECTURE IN THE AGE OF ‘MESSY MEDIA’ by Helen Castle Executive Commissioning Editor at Wiley Editor of Architectural Deasign (AD) @hecastle | @AD_books This article is based on a lecture first given on 27 November 2013 at the University of Greenwich and then updated and expanded for presentation at SALT Galata in Istanbul on 29 May 2014. 16 It used to be so simple. Ten years ago, an architect finished a project, won a design competition or completed a building and they sent it to an architectural magazine to be published. It was a matter of coming up with the stuff, knowing the right editor, sending it off to them and then following it up with a phone call, or even a boozy lunch. It was all about influence, connecting with the right people, and perhaps a bit of flattery, but the decision of how, what and when you got published was ultimately out of the architect’s hands. Other people were responsible for the media – journalists, critics, editors and broadcasters. Though traditional publishers and broadcasters still remain in control of a good portion of the media – print, electronic, online, TV and radio – the widespread adoption of social media has shaken everything up. Power has devolved. We have all become individual generators, curators and disseminators of our own and others’ content. The huge array of choices that social media provides can be bewildering and overwhelming. For many, it is so debilitating that is an excuse to do nothing, or very little. Who would go into an overstocked supermarket and just because there is so much choice of food on the shelves, come out with an empty trolley, and go hungry? For architects, not engaging in social media in a knowing and considered way makes all the difference between getting their work out there and getting noticed, or remaining entirely unnoticed. 17

ESCAPING THE BASEMENT Perry Kulper is an architect and Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of Michigan, who has become well known for his beautiful and inventive architectural drawings; he contributed an article to Neil Spiller’s September 2013 issue of Architectural Design (AD) ‘Drawing Architecture’, and this year he was invited by Eric Parry to display two of his prints in the architecture room at the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. (1) Five years ago, Perry started posting his drawings on Facebook in order to show a faculty friend from SCIArc what he was working on and as an alternative to setting up his own website. Perry describes his approach to Facebook as one of knowing caution: ‘I was, and probably remain, wary. It’s the nature of me working quietly in a basement here in Ann Arbor, or in a small work space in our house in LA, essentially by myself. Virtually all of the drawings are design worksheets to develop things and are not intended to “be in the world”.’ (2) It was, however, this experimental and exploratory nature of Perry’s work that captured people’s attention and imagination. As he says: ‘I received Facebook messages from people all over the world wondering about how I make drawings, saying they like them, many faculty have said they use the drawing images to expose students to what drawings might do, it has allowed some publications of some of the drawing images.’ Perry has 2,500 Friends on Facebook and commonly gets a hundred or so likes in response to a post. This development of an immediate audience for his work has in turn made him more responsive or media savvy: ‘I do think that partially as a result of getting things out into the world just a little that I am more conscious of a set of factors now that “exceed” me simply working on the work – audiences, how something might print (if there was eventual interest), what people in fast social mediums make of the work, etc.’ (1) Perry Kulper, ‘A World Below’, Neil Spiller (guesteditor), Drawing Architecture, Architectural Design (AD), John Wiley & Sons, September 2013, pp 56–63. (2) Email exchange between Perry Kulper and the author, May 2014. 18 Perry Kulper, Thematic Drawing, Central California History Museum speculative project, 2001: as featured in Drawing Architecture 19

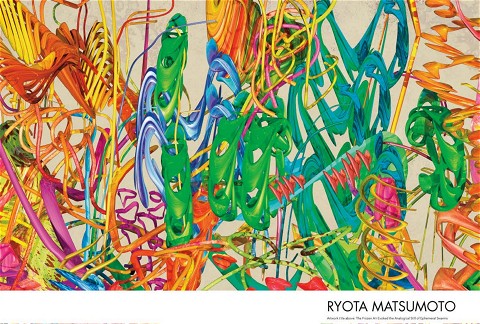

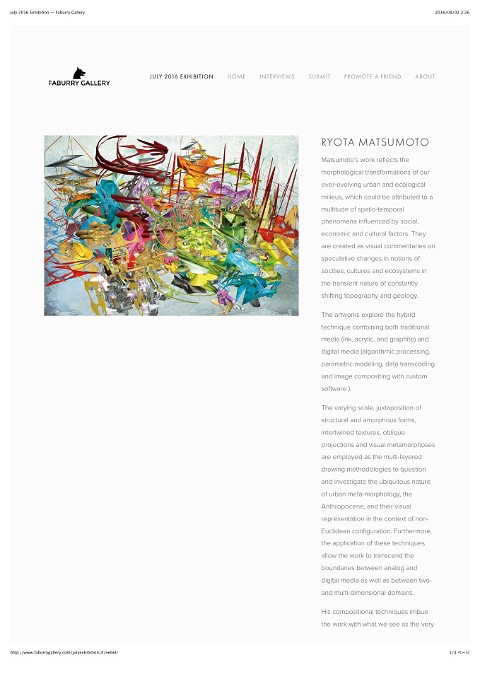

Ryota Matsumoto, Pharse-shifted Ember (mixed media on paper), 2009. If Facebook helped Perry get his work out of the basement, it has provided Japanese architect Ryota Matsumoto with an alternative creative outlet from his day job; Ryota is the principal of his own practice Ryota Matsumoto Studio in Tokyo. He started using Facebook and LinkedIn around the middle of last year to keep in touch with friends and mentors in Britain and the States who he had met while studying at the Architectural Association and the University of Pennsylvania.(3) Ryota began by posting built work but was encouraged by friends to post his old student ink drawings and then recent colour images. This enabled Ryota not only to reconnect with the likes of David Turnbull and Jane Harrison, who he knew from his studies at the AA, and Winka Dubbeldam from Penn, but it has also given him the opportunity to extend his network and get to know a new group of international designers, such as Perry Kulper, Bryan Cantley and Attilio Terragni. As a consequence, his recent coloured work has gained momentum. He now not only has a sizeable reach on Facebook with over 3,000 friends, but since the end of last year has been working on drawings for Italian and Spanish publications. He also has a travelling exhibition of some recent work in Italy under way. 20 21

GETTING ‘MESSY’ What is interesting about both Perry Kulper’s and Ryota Matsumoto’s experiences of social media is that both of them regard it as a route to traditional publishing. It is not a matter of either or. I work as a commissioning editor on the architecture programme at Wiley, London. This means I approach authors to write books and then work with them to develop manuscripts for publication. In this capacity I also edit AD, which entails commissioning six guest-editors a year to edit an issue of AD around a particular theme. Wiley specialises in knowledge and knowledge-based services in areas of research, professional development and education. Fifteen years ago, Wiley led the way in electronic publishing by creating Wiley Online Library, a dedicated platform for its extensive portfolio of journals, and is now a key provider of e-learning digital solutions. What I still though predominantly do for my part at Wiley is page based: I publish print and electronic books and journals. Publishing is on the frontline of shifts in media. Whereas people used to get all their information from printed books, magazines and papers, there is now a wide variety of sources available to them online and often for free. This means publishers cannot afford to bury their heads in the sand and carry on just as they were before. Some far-reaching thinking and changes are currently taking place. This makes it both a nerve-racking and also an exciting place to be as you have to constantly question what you are doing and how to proceed. So this has all led me to think a lot about communication in architecture and also the media, and why and how it is important for architects and students of architecture. For me this article and the lectures on which it was based have been a great opportunity to formulate some initial thoughts around the subject. As soon as I started to research and think about this subject it became apparent that neither communication or the media are nearly as messy, perplexing or arbitrary as we often characterise them to be - thus the ‘messy’ above is in quotation marks. Certainly, the changes in the way content is now disseminated have been fast. The World Wide Web only came online just over 20 years ago, Facebook 10 years ago and Twitter eight years ago. iPads have only been around for just over three years, since the Christmas of 2010. 22 this sense that we believe things might be out of control or have a life of their own. We talk about stuff going ‘viral’ over social networks - giving a sense of ‘infection’ or ‘contamination’. We also talk about ‘memes’ – those often humorous images, videos, bits of writing that are copied and spread so rapidly by internet users, with slight variation, that they are likened to genes in the way that they self-replicate, mutate and respond to selective pressures. In fact it is the individual rather than the content that is very much in control. Whereas traditional broadcast media, such as TV and radio, used to broadcast at its audience so communication was one way, individuals are now able to participate in the circulation and shaping of stories and images. When we choose to respond to posts on Facebook or Twitter, for instance, by sharing and commenting it is far from passive – it is a decisive and some declaration of our beliefs, likes, humour and interests. Someone, who has done a lot of interesting research around this subject, is Henry Jenkins, Professor of Communication at University of Southern California, formerly at MIT. Jenkins did a lot of work on fan culture and gaming in the 1990s and 2000s that in a sense has anticipated the participatory culture that is more widely experienced today through Facebook, Twitter LinkedIn, Pinterest, Tumblr and Instagram. Jenkins has contested the use of the word viral and memorably characterised new media as ‘spreadable’ like peanut butter, ‘sticky’ as it spreads.(4) But why is a discussion of communication and the media relevant to students of architecture and architects? You might think that architecture is all about design and imagery, conveying your ideas visually – whether it is in 2D or 3D. Isn’t it after all what students dedicate all their time to at architecture school? Visual representation is a major component of architectural practice – but it cannot stand alone. LANGUAGE & ARCHITECTURE A VISUAL RESPONSE TO A TEXTUAL NARRATIVE In an industr y where objectivity and interpretation balance precariously, EDGEcondition were inspired to showcase these var ying insights by inviting different creatives to respond visually to a text written by archipoet Ted Landrum. The second part of this article by Helen Castle will appear in our next issue, Art and Architecture, out in September ‘14. 23